The mission of this public art project is to elevate how a community sees itself and is seen by others.

This project is funded in part by a grant from the Fitchburg Cultural Council, a local agency which is supported by the Mass Cultural Council, a state agency, and by NewVue Communities.

Ricardo Barros

Photographer

This project was born when I saw a photograph from the Fitchburg Art Museum’s collection. It was Jules Aarons’, and he photographed street life in Boston’s West End during the 1940s and 50s. His subjects’ settings closely resembled what I saw on a near-daily basis in downtown Fitchburg. But unlike Jules’ photographs, Fitchburg’s Main Street seemed empty. Many storefronts were vacant, and street life was conspicuously missing. Granted, people no longer congregate outdoors as they did in the 1950s, but one’s impression was that Fitchburg was barren. And I knew this not to be true.

Artists move where they can find affordable studios, often revitalizing depressed communities. I am an artist. I had recently moved to Fitchburg. My early response to the perceived emptiness was that if I could reach other artists, they, too, might move to Fitchburg and accelerate the city’s rejuvenation. So, in what turned out to be my first photograph in this project, I literally put three artists on the street and made their photograph. This group portrait represented my vision for Fitchburg’s salvation.

But then I realized what I had missed. There were people in the buildings; we just couldn’t see them. And many of these people had done—or were doing—remarkable things. If I couldn’t drag them all out to the sidewalk, I could at least shine a light on their presence. As one Fitchburg person referred me to another, their number and robust network became visible. Only a few of the people I met were artists. But the passion, agency, and accomplishments of the people in Fitchburg today are laying a promising foundation for Fitchburg’s future. These people, many newly my friends, deserve to be seen.

Peter Capodagli

Historian and Collector, Boulder Art Gallery

Peter Capodagli was born and raised in Fitchburg. He earned his degree at Fitchburg State University and taught science locally for 35 years. Upon his retirement, he and his wife, Ann, opened the Boulder Art Gallery on Main Street, displaying works by local and regional artists. Peter is also a history buff and a passionate collector of Fitchburg memorabilia, having a particular interest in an entrepreneurial giant from the late 19th Century.

Iver Johnson, a 22-year-old Norwegian immigrant, arrived in this country in June 1863, one week before the Battle of Gettysburg. Trained as a gunsmith, he quickly found employment in a Worcester, MA, arms factory supplying the Union Army. No ordinary technician, Iver Johnson brought initiative, inventiveness, and an entrepreneurial spirit to his craft. Impressively, he and a partner founded their own manufacturing business within eight years of his arrival. But Iver was not content producing less than perfectly designed equipment. This inner drive led him to patent several mechanical innovations, cementing his reputation for quality work. Iver Johnson went on to acquire his partner’s interest and subsequently diversified his product line to include bicycles. His company would eventually be known as the Iver Johnson Arms & Cycle Works.

Iver Johnson Arms & Cycle Works began manufacturing bicycles of Iver’s design in 1885. His timing was fortuitous, as a bicycle craze was about to sweep across America. Within a few years, bicycle races would draw thousands of spectators. The company would eventually sponsor cyclist Marshall Major Taylor, the first African-American to break the United States’ color barrier in a national sport, preceding Jackie Robinson’s achievement by 48 years.

In 1891, when Iver Johnson’s Arms and Cycle Works moved to Fitchburg, production reached 15,000 bicycles yearly. The factory would occupy 200,000 square feet, house state-of-the-art equipment, and employ metallurgists and skilled craftsmen on the production line. This manufacturing facility was one of the largest in the world at that time. With his wealth ever-growing, Iver Johnson moved his family to a lovely home at 131 Highland Avenue in 1893. The company’s growth and prosperity continued under the leadership of his eldest son, Frederick, after he died in 1895.

Iver Johnson’s bicycles are now highly sought-after collectibles. As of the last count, Peter Capodagli has restored three and keeps more than forty others in storage. These bicycles are his pride and joy.

Steve Duvarney

President, The Fay Club

When Steve Duvarney’s grandfather opened his family jewelry store in 1970, his was the fifth jewelry store in downtown Fitchburg. Steve’s grandfather found clients through The Fay Club, a private dining association where community leaders networked with peers. The Fay Club had a storied tradition of hosting mill owners, bank presidents, doctors, and lawyers. Built in 1883, it was a testament to Fitchburg’s grandeur.

The Fay Club’s prosperity aligned with Fitchburg’s. As paper mills closed in the late 1900s, membership declined and the Club became increasingly less profitable. In 2015, all hope seemed lost. The Board prepared the building for sale.

Steve Duvarney has been a familiar face on Main Street since 1987 when he started working for his grandfather. (The family jewelry store is now his, at the other end of Main Street.) His bond with The Fay Club, its members, their culture, and the Club’s Victorian architecture runs deep. The thought of selling the building was unbearable to him.

Steve mobilized a handful of Club members to execute a desperate plan. Assuming the Club’s Presidency, Steve and his allies renegotiated bank loans, slashed membership fees, broadened their business model, and tapped volunteer labor. Quietly, anonymously, some in the group also reached into their pockets to cover inevitable shortfalls. The Club is now a regional magnet. It draws patrons from Concord, Groton, Worcester, and beyond. It successfully addressed capital expenditures and operating costs. It is well on the road to a self-sustained future. The Fay Club remains a private club, yet it wholeheartedly welcomes new members and guests.

Steve Duvarney continues to volunteer his time to the Club on a near-daily basis. His is a labor of love, driven by passion. He appreciates history but knows The Fay Club manifests more than tradition. It embodies long-lasting relationships. It is a place where friends are willing to step up when their community needs help.

Andrew DeChristopher and Tristan Taylor

Founders, Fitchburg Fiber LLC

Tristan Taylor was outraged. It was late 2020, the Covid lockdown was starting to lift, and schoolchildren had no choice but to attend classes online. The problem was internet access. One mom with four kids was facing a $180 monthly bill from her internet provider, which she could not afford. The company shut off her service. “Libraries were closed, school systems couldn’t provide hotspots yet, and people were flocking to the mall, to McDonald’s, anywhere that had public WiFi,” Tristan says. “That boiled my blood.”

Tristan Taylor is a generalist with formal training in Geographic Information Systems. By chance, his then-employer assigned him to work remotely with a like-minded colleague, Andrew DeChristopher, a software engineer specializing in computer networking. Without ever meeting in person, the two discovered shared values – and outrage with companies providing critical utilities motivated purely by profit. “Why don’t we do something about it,” Andrew proposed. They put a business plan together and met face-to-face for the first time at a bank, where they opened a joint account and signed documents creating Fitchburg Fiber.

Fitchburg Fiber’s mission is to provide internet access that people can genuinely afford. “This is the right thing to do,” Tristan says. “But we were a brand-new start-up with zero revenue,” Andrew adds, “and installing fiber optic cable under streets downtown is prohibitively expensive … to the tune of $1,000 per foot in some cases.” So, the two resorted to wireless technology. They purchase high-bandwidth directional radio links and install them on rooftops at their own expense. Each radio node can see others nearby, creating a dense mesh of signal coverage.

Their next challenge was to claw a sliver of market share from their Goliath competitors. While their budget could not compete with those of Verizon and Comcast, they discovered a chink in their competitor’s armor. Cable did not reach certain parts of Fitchburg. Starting there, Fitchburg Fiber now serves a territory roughly one mile long by half a mile wide in Fitchburg’s downtown corridor. And this for a price tag of approximately $200,000 – straight out of the founder’s pockets.

At first, Tristan and Andrew kept their full-time jobs, each devoting another 40 hours per week to Fitchburg Fiber. Now Tristan is “full-time unemployed,” meaning he works only for Fitchburg Fiber. Andrew pays the company’s bills with his second job. Both still work brutal hours, whether installing and maintaining hardware, recruiting customers, providing customer support, or doing office-related work.

Unlike their competitors, who offer low introductory rates and raise the monthly fee soon after, Fitchburg Fiber’s monthly payment is locked. Forever. “We charge $40 per month,” Andrew says, “and we want to lower that price over time.” “Our long-term goal,” Tristan adds, “is to build efficient fiber to cover all of Fitchburg and then transition it to a community cooperative where the customers are the owners. We are already building an excellent infrastructure and provide outstanding service. Fitchburg Fiber will eventually be a self-sustaining public utility impervious to the profit motive.”

Jennifer L. Jones

Composer

“Music is a universal language,” says composer Jennifer L. Jones, seated at her Steinway piano in the elegantly restored mill building, The Yarnworks. Paintings, prints, drawings, and photographs fill her walls—or at least as high as a person can reach vertically. “Music is an expression of love. It heals, brings joy, and embodies a chain that pulls us together.”

Jennifer received her first piano lessons from a neighbor at age 9. Now, more than ever, she appreciates the gift. She studied at the Boston Conservatory of Music and became a music teacher. “I loved teaching music. That experience led me to become an advocate for high-quality arts education.” During this time, she stopped playing the piano for herself.

“When we moved to Fitchburg in 1988, I got involved with the community by giving private music lessons to neighborhood kids.” Lots of them came from low-income families. Fitchburg has diverse neighborhoods, and, in some cases, schoolchildren had to translate for their non-English speaking parents. “They loved music, just like everyone else.” When Jennifer became a music teacher in the public schools the following year, she realized that extracurricular challenges impaired these children’s academic achievement. She felt compelled to make a still more significant contribution.

Assuming the role of Director of Arts for the Fitchburg public schools, she championed after-school enrichment programs. “My primary goal was to provide access to arts education for all children during the school day and after school with the hope of closing the achievement gap for struggling learners in reading and math.” Jennifer opened after-school sites at each public school in Fitchburg. At one point, we had 500 kids participating at ten sites. Our program wasn’t about more academics; it was about enrichment. We would integrate music, art, puppetry, and theater into their experience. And it made a difference. We were able to close the achievement gap for more than 85% of participating children across the district.”

After retiring in 2016, Jennifer returned to her first love, the piano. This time, her approach was different. She didn’t want just to play music; she wanted to create it. She became a composer. She has since struck her creative stride with an impressive collection of original pieces. “I am back to practicing the piano and listening to the music of emerging artists and composers. It is a thrill to have my music streamed worldwide!”

“The piano can kindle feelings of peace and joy,” Jennifer L. Jones says. “I just finished a composition called ‘Castles in the Sky.’ I love the image of castles floating above the clouds, drifting, slipping in and out of the mist. It’s another world. It seems so distant and yet so familiar. That’s where music can take you.”

Mayor Sam Squailia

Fitchburg Mayor

It was 9:20 PM when her email came in. Mayor Sam was working late again. Sam Squailia was confirming a follow-up interview to a portrait I had taken of her wearing high heels – and pushing a wheelbarrow. I had been hesitant to propose that photo concept to her; I hardly knew her at the time. What I did know was the impression she had made on me: hers is a can-do spirit brimming with confidence, agency, and a sunlit smile. We would meet in her office.

“You seem to attend every event in Fitchburg, manage an administration, and you’re a mom. What is your typical day like?” I ask.

“I get here around seven after I drop off my daughter at the bus. Sometimes later, if I’m meeting someone. On a typical day, I meet with constituents and Department heads to solve problems. City Hall closes at 4:30, but I don’t leave then. Sometimes I go to a meeting at 6 or 7 PM. On Mondays, I stay late and whittle the email queue as close to zero as possible. I usually go to three or four events on Saturdays. Sundays are my day off. I get to do our laundry then. Oh, and I did a ride-along with the police on Friday. I was up until around 3:00 AM.”

“This sounds brutal. Have you always been interested in Civil Service?”

“No. But people recognized that when I got involved, things got done.” With considerable encouragement, Sam Squailia ran for City Council. “I was elected and served for six years. I love talking to people and working things out. But the Mayor gets to decide important things, and I had different ideas. So here we are.”

Mayor Sam was elected Mayor in 2023. Not quite one year in office, she is aware that the decisions she makes now will have a lasting impact on the city’s future. Yet, she wrestles with difficult choices. For example: “Our landfill used to generate revenue for us. It paid for itself and could offset the cost of curbside collection. It’s not doing that anymore. The landfill will close in five years. What are we going to do from now to then? No one wants to raise taxes or fees, but we can’t continue on this trajectory and still provide the services that the city needs.”

“How can you possibly address that?”

“I can’t do it alone. Listening, understanding the issue, and working collaboratively is key. Direct, unfiltered communication is also essential. Through social media, for example, my constituents have informed me that an underground pipe burst before our Water Department knew about it.”

Pausing to reflect on her constituents, Mayor Sam adds an appreciative afterthought. “We have an awesome community. They pitch in. They’re generous. We may not have a lot, but we give a lot.”

Zachary Bos, Bookseller

Bonfire Books, Goldfinch Mercantile

“This is Zak, who read the books.”

That is how Zak was introduced by his 5th-grade teacher to one of her colleagues. Coming from a home of modest income in Patterson, NJ, Zak hungrily latched onto whatever resources he could, including reading the entire World Book Encyclopedia. Twice. Today, Zachary Bos is opening two bookstores in downtown Fitchburg: Goldfinch Mercantile, a retail shop offering new titles and the second, Bonfire bookshop, a combination retail-office space, offering used and antiquarian books. The latter will include amenities for visiting readers: a coffee bar, soft music, and patio seating. “This will be a relaxing retail destination.”

Zak’s world is indeed comprised of words and ideas—just listen to him speak; his language is eloquent, and he expresses himself in paragraphs—but his dreams are also empowered with agency. “I’ve always been a writer,” he says, seated among shelves and inventory in a temporary warehouse. “I never thought of it as a career path because it didn’t feel like the responsible thing to do.” So, he created a path for himself, not just for his success but to uplift others. “I engage to catalyze, uplift, and multiply. If I help 10 people increase the success of their work by 10%, that’s 100 percent.” He still does this, and now he also has his own publishing company, Pen and Anvil Press. Without capital to launch his bookstore project, he had to “ask people for the money. I brought people in on the train. I put them up for a week or a weekend. I showed them the bright windows and the dark windows.” He shared his vision. They saw the opportunity. “Fitchburg is poised for growth.”

Historically, Fitchburg was, and will be again, a regional center for culture and the arts. His bookstores will be part of that. “Why are we funding the arts? We need jobs. The arts build stories, and stories build hope. Hope brings investment. Investments bring jobs.” Zak wants to provide bookstores “where everyone in the community can find their stories. I am not a hobbyist trying to turn it into a profession. This is a business. I want to provide a livelihood for myself and three or four people involved with the business.”

“Public perception, even self-perception, of Fitchburg must change. Most residents take well-deserved pride in the city’s history, and too many outsiders conjure economic downturn at first mention of the city’s name. These perspectives are rooted in the past. The stories cling to the teller. That narrative space is dominated by people who say, ‘I remember when …’ But artists look to the future and aren’t bounded by limited imagination. They push through cynicism. They’re undaunted.”

With two bookstores about to open, Zachary Bos undauntedly participates in the creative economy poised to surge through Fitchburg.

Chief Ernest Martineau

Fitchburg Police Chief, retired

“I’m going to be just like you someday.”

Police Chief Ernest Martineau lived on Elm Street, less than 1/8th mile from BF Brown Junior High School. “In the 70s, your neighborhood was everything. Back in those days, you knew everyone who lived around you. At 7:00 at night, you could hear everybody’s mother yelling from the porch, ‘Time to come home!’ My mother was a single parent raising two kids. She had two jobs. We started off on the 3rd floor of a triple-decker apartment building on 399 Elm Street. As tenants changed, we moved down a floor so my mother wouldn’t have to carry groceries up the stairs. When we finally made it to the first floor, it was like we hit the lottery. It was a big deal.”

In 1979, Ernest Martineau was a ninth grader at BF Brown. “That school is truly near and dear to me. I was Captain of the football team and Student Council President. I was actively involved in putting our school dances together, and we would hire a police officer to chaperone. At one particular dance, I became enthralled with policing and spent most of the night talking to Officer Peter Roddy, the police officer hired for the event, and not participating much in the dance. ‘I’m going to be just like you someday,’ I told him.” Sure enough, Ernest Martineau became a policeman upon graduation from college and rose to the rank of Fitchburg Police Chief in 2015.

“I’ve had to make some tough decisions over the years, but if you stay focused on your mission, it’s not that difficult. You can bring a compassionate side to police work. I refer to the three T’s of policing. It begins with Trust. Having trust in the community. The second is Transparency. Transparency allows the community to trust the police. And third is Teamwork. The police and the community have to work together.”

There was civil unrest throughout the country after the George Floyd incident in Minnesota. “We had three to five thousand people demonstrating on Main Street. We were one of the very few demonstrations in the State that had zero disruptions. The demonstration went without a hitch. Everybody respected each other’s space. It was actually a wonderful day where people had an opportunity to express how they felt. We were there to make sure that they felt safe, that we felt safe, and that there were no disruptions. That said a lot about our community on that day.”

Back in the day on Elm Street, “We didn’t have a lot of money, but we had a sense of ownership in our community. I’ve seen a lot of transformation in the city over the past several years. One of the biggest is where we started creating homeownership opportunities in the neighborhood. That needs to continue.” “And now, with the conversion of BF Brown into affordable housing for artists, there are going to be dozens of apartments supporting the regional arts community. I can’t think of a better use of my old school building. It is extraordinary.”

Jim Desrosiers

Founder, GROWTHco

At age 14, Ron Bouchard, who later became known as “The Kid from Fitchburg,” was tapped as a last-minute substitute driver for his father’s race car at Brookline Speedway. Still in high school and too young for a driver’s license, The Kid won the race. His professional achievements accelerated from there. He claimed five consecutive championships from 1967 to 1971 at Seekonk Speedway. In 1981, Ron won the Talladega 500 in NASCAR’s highest division by a hair in a three-car photo finish. Racing aficionados consider this win the biggest upset in history, and it clinched NASCAR’s Rookie-of-the-Year honors for The Kid.

Success continued throughout his career and Ron Bouchard was a special kind of champion. He was mindful of his impact on his fans. Following his victories, Ron would pose in group photos with kids from the crowd, sometimes gifting a lucky child the trophy he had just won. Ron believed in them, and he wanted them to believe in themselves.

Jim Desrosiers, also from Fitchburg, was one of those kids. Jim had been traumatized by an alcoholic father, domestic violence, abuse, and poverty. If statistical expectations held, Jim’s prospects were bleak. The winning race car driver was a distant beacon, a glimmer of possibility. “If he’s from Fitchburg and can succeed, then maybe I can, too,” the young boy thought. Jim’s life took a turn for the better when his mother remarried. His new dad enveloped Jim in safety and love, and then military service forced Jim to realize his capabilities. But Ron Bouchard, The Kid from Fitchburg, kept the child’s hope alive when he needed it most.

Jim was working as the Director of Development at the Fitchburg Art Museum when he finally met Ron Bouchard. Together, they raised money to help local nonprofit organizations and formed a close relationship. Ron became Jim’s mentor, confirming what Jim’s vocation would be.

Jim Desrosiers helps others. Jim went on to found GROWTHco, a training and development firm. He helps individuals and organizations grow and thrive. Through structured measures, he enables clients to harness their potential, optimize success, and manifest fulfillment.

Ron Bouchard’s passing from cancer in 2015 swept Jim into deep reflection. He understood that legacy is the vehicle passing values from one generation to the next. Jim and the Bouchard family created the RB Racing Charity to help families with their cancer experiences and to support positive youth activities.

Jim Desrosiers is now planning a bronze memorial depicting The Kid from Fitchburg mentoring a young boy. It is to be sited at Fitchburg’s Coolidge Park. Vulnerable children may see themselves as that child, and Jim hopes we adults will see ourselves as Ron Bouchard.

C.M. Judge

Artist

Artist C.M. Judge and her husband, John Heimo, live and work in an 1889 schoolhouse. The West Fitchburg Grammar School sits on a hill overlooking former mills on the North Nashua River. Walking its grounds, one can almost hear laughter as Kindergarten through 6th-grade girls “jumped rope, played hopscotch,” and boys played “rag ball between the buildings and kickball on the west side of the building,” according to alumni from the mid-1900s now on social media. But not all recollections are so cheerful. Another alum recalls a teacher who “liked to grab students by the ear” as a disciplinary measure.

“The generosity of sharing information doesn’t necessarily match the generosity of spirit,” C.M. tells me in a very different conversation about art. We were speaking of teachers and ideas embedded within an artist’s work. It is fitting that C.M. and John, both former teachers with far more helpful perspectives, now reside in the schoolhouse. They bought it in 1997 and have been working on it ever since. C.M. has converted one of the spacious rooms into her studio.

C.M. Judge is an internationally recognized artist with exhibits in France, Germany, Uruguay, The Netherlands, Japan, and the United States, many of them with collaborators. She received extensive formal training and earned a Master of Science in Advanced Visual Studies from MIT. “I work with 2D, 3D, and time-based media. I call myself an intermedia artist because my works do not arise from the medium; they evolve through ideation.” In other words, she is open to alternate forms of expression and chooses the form and expression most appropriate to her latest thinking and the project’s needs. Through imagination and collaboration, she paints on the canvases of people’s minds.

I ask C.M. if her artwork is concept-driven. “I think I may just be a responder,” she replies. “I’m someone who strives to feel the world deeply, understand the human condition and understand what empathy looks and feels like for another person. And that gets translated into this a visual or auditory expression.”

I see four monochrome faces on her studio wall, each manifesting a different emotion. “Those are from a series called ‘At Core’ that I developed after my son was born. Watching a newborn is a meditation on the human spirit. They don’t have a mask. Every expression is immediate and authentic. It is what they are experiencing.”

Generosity can take many forms. C.M. smiles as she tells me a story about when she first arrived in Fitchburg. “A package from my collaborator in Japan was delivered to my house. I didn’t think anything of it. At 5:00, the mail carrier knocked on my door and said: Did you get your package from Japan? I’m on my way home and just wanted to make sure you received it.”

Not all our social interactions may be kind, but kindness prevails when permeated with C.M. Judge’s generous spirit.

Nate Glenny

Director, Fitchburg Access TV

“All the experience I’ve acquired as a professional I’m bringing back to the place of my foundation.”

The young boy’s heart swelled as he toured Fitchburg Access TV (FATV). “The medium, the technology, and the power to speak to so many people in their living rooms was overwhelming.” So says Nate Glenny, the former fifth grader who was awarded a tour of the television studio after being selected Student of the Month. His path was clear from that moment on. Arriving as a volunteer, he worked his way up from being a runner (running miscellaneous errands) to a cable-puller (wrangling with cables and gear) to a camera operator. As a professional, he has worked for virtually all networks and professional and college sports teams in New England. Adult Nate couldn’t believe his good fortune; he was living his life’s dream. What could be better?

Then, he raised the stakes. In 20xx, already on the Board of Directors, Nate returned as Director of FATV. The scope of his concerns grew from being a doer to being a leader. He guided the design and construction of a new, state-of-the-art video production facility, including video and podcast studios, cameras, sound systems, and related software.

As for programming, “We are Fitchburg’s greatest cheerleaders,” Nate says. “Naturally, we cover public meetings. Local sports are especially popular. We cover graduations and awards ceremonies. And very significantly, we televise programs produced by our members.”

Several features distinguish FATV from commercial broadcast stations. “We are a membership organization. Anyone who lives or works in Fitchburg can become a member for $40 per year. You can access all the equipment, studio, Adobe software, training, and channel time to produce your own show for that fee. Anyone who wants to produce positive, nonprofit programming is welcome here. Our principal distribution outlet is the FATV cable channel, and we push video and podcasts onto Apple, Amazon, and Spotify. Plus, unlike online social media, we are not content controllers. We don’t sieve our content through algorithms and data metrics.”

“FATV is one of Massachusetts’s more active local TV stations.” And, thanks to its staff and facilities, it is one of the most professional. Depending on how one counts, FATV has a staff of five to ten full-time, part-time, and volunteer workers. “Our staff can only produce a certain amount of content, yet that is not our primary goal. We want members to produce content. Our core function is to engage and empower our community, and to teach members how to use our equipment.”

FATV does not aspire to speak for the comunity. FATV aspires to be the medium through which the community speaks for itself.

Barry Slome

Somewhere, on a side street in Fitchburg, you may find a man seated on the ground, fixing a bicycle. Not one bicycle, but many. Should you stop and talk with this man, you will find that he is at peace with himself. There is clarity in his purpose. Although there is little risk your conversation will address existential concerns, it will be sufficient unto itself. All is as it should be. The reasons why are superfluous.

Barry Slome fixes broken and derelict bicycles. “It keeps my hands occupied,” he says. “It’s not that I love to fix bicycles. It can be very frustrating. It’s dirty, my hands get filthy, especially handling the oiled chain, and they’re not always easy to repair.” Despite intentionally keeping a low profile, Barry and his passion are known to many in the city. He does not advertise or participate in social media. His address is private. He rarely seeks out bicycles for repair; they are mostly brought to him. “I try not to get into the newer bikes,” he says, “I like the old ones, from the 70s and 80s. That is my preferred vintage. They were simpler.” For Barry, “simpler” goes hand-in-hand with “clarity.”

Barry’s family has lived in Fitchburg for generations. As a kid, he went to BF Brown Junior High School, a building now being converted into affordable artists’ residences. “My first bike was a 20-inch Columbia. Later, my father bought me an English bike, a Dunelt. It had a leather saddle.” At the age of 10, “I rode that bike from my house to Cleghorn. My friend had a grandmother who lived there. That’s all the way across town. It was a real trip, an adventure.”

Now, he fixes bicycles and sells them to the occasional visitor. “Tell me what you want, and I’ll have something to show you tomorrow,” he says to them. His storage bays are filled with bicycle parts. “I don’t care if it is a cheap or expensive bike. They’re all nice to ride. If it is a nonworking ten-speed, I’ll take one of the chainrings off a rail and turn it into a five-speed. That’s all you really need.” Looking over his shoulder, he adds, “The one I rode today is an old-style single-speed.”

“I never wanted to work in a conventional job in an office or in a store,” Barry says. “And I’m not a professional bike mechanic.” While he doesn’t use these words, his is a labor of love. Bike repair is “not an income-producing thing for me. If I sell a lot of three or four bikes, it all goes to my storage fee. It doesn’t go into my pocket. Money isn’t my goal in life.”

“I like the simplicity of things. I hate to see a bike scrapped, even a low-end bike. You know it’s useful to someone. Or it could be.”

Audrey Pendleton-Chow

Director, Curious Escape Rooms

Audrey Pendleton-Chow can’t help but get involved. Her enthusiasm just won’t be suppressed. Mostly out of curiosity, she attended a public input meeting presented by the Fitchburg Cultural Council in 2017. It was not a large meeting. Seeing a new face, Council members asked how they might get more people involved with them and Arts & Culture in the community. “Start a Facebook Group,” Audrey suggested. “We don’t know much about that,” Council members replied. “I can start one for you!” Audrey heard herself say. She has since become the Council’s Chair.

“Sometimes you have a vague idea of the goal,” Audrey says, surrounded by VHS tapes. “You’re not sure what the goal is going to look like, you’re not sure how you’re going to accomplish it, and there will be different puzzles you have to solve along the way.” Here, she is not speaking of her work for the Council. She speaks of the challenges in escape rooms, like her interactive art installation – a fake video store.

Curious Escape Rooms, a unique venture started by Audrey and her husband, Jeremy, in 2016, offers immersive game experiences that transport you to worlds that invoke a sense of nostalgia and wonder. The 90’s Video Store is one such creation. (Curious Escape Rooms offers other games and variant scenarios under the same roof.). Players come from Boston, Rhode Island, New Hampshire, Vermont, and Eastern New York to wrestle with existential riddles in an allotted amount of time.

“You have to find a secret videotape before the boss comes back!” Audrey says, explaining the challenge of her fake video store game scenario. “That’s all you know. You’ve been called, and we need to find it before the boss returns.” The beauty of such a game is its tantalizing ambiguity. Players must play the game to discover its internal logic. In other words, players must play the game to learn the game’s rules. This game is a team sport; people work together to “escape” a looming consequence.

And so it is for creative small businesses such as hers. One must first explore the room to discover unseen constraints, then cobble together a plan circumventing whatever obstacles one encounters. For example, a challenge facing storefronts in Fitchburg’s central business district is the district’s size. The main drag is nearly one mile long. Even with a fair number of businesses operating there, they are spread out, seemingly disconnected, and create an impression that Main Street is barren. Audrey knows it is not.

Audrey is a team player. She voluntarily compiled a spreadsheet of downtown businesses so each could keep others informed of their programs, opportunities, and concerns. Audrey also produced a map identifying each company and its location, promoting retail activity. And she installed a public bulletin board where anyone could post a flyer announcing their event.

Audrey Pendleton-Chow is passionate about solving puzzles. As with her Curious Escape Rooms conundrums, her enthusiasm is infectious and much to the community’s benefit.

Bill Flynn

Fitchburg Mayor, 1968-1971

Marion Stoddart

Founder, Nashua River Watershed Association

Bill Flynn was fascinated by the first-ever broadcast of the Democratic National Convention as a young boy. Civic service called him. He ran for and won a Fitchburg City Council seat at 22. “But the Council wasn’t focusing on the big issues,” he says, so Bill ran for Mayor at 25. Fitchburg was grappling with poor governance, a lack of regional engagement, and experiencing a severe drought.

A polluted Nashua River running through downtown Fitchburg was the background to all this. The Nashua River in the 60s “was unsuitable to transport waste,” Marion Stoddart says. “If you stood on a bridge and threw in a big rock, it wouldn’t sink. The river ran different colors every day. And it smelled like rotten eggs. It was one of the ten most polluted rivers in the United States.”

Marion Stoddart, then a young mother of three, had arrived in nearby Groton in 1962. The Nashua passed near her home, downriver from Fitchburg. Her move to Groton was an opportunity to reflect on her life. Marion asked herself, “Why am I here? What is it I’m supposed to be doing?” Her answer: committing herself to “taking on the greatest challenge I thought I could accomplish in my lifetime.”

“The most change comes from outsiders,” Bill says, “because when you’re in the thick of it, you don’t see the problems.” Marion appeared at a City Council meeting and spoke of the river’s pollution. Responding to her initiative, the Council funded a restoration feasibility study. Following that, Bill continues, “I put all kinds of miles on my car traveling to Boston, wrestling with the bureaucracy. If you didn’t push this thing, it wouldn’t happen.” The two worked tirelessly to pass State legislation, tightening standards for industrial discharge, building grassroots support for the river, and battling misconceptions. (One mill owner reportedly asked its employees, “Would you rather have clean water or your job?”) Bill and Marion subsequently helped persuade the City Council to issue a $27.5 million bond in 1970 to help clean up the river. “That was like twice the existing city debt!” Bill remembers.

“Now, it is a wonderful recreational river. People are canoeing, fishing, and swimming,” Marion says.

“Fitchburg was a national leader in the effort to clean up the environment,” Bill proudly states. “Marion was a champion of the process. Once Fitchburg turned the switches, all the other sins started to show up. Downriver, they couldn’t hide it anymore.” And the Nashua River Watershed Association was an outgrowth of Marion’s efforts.”

“We couldn’t have done this without Bill,” Marion Stoddart says.

“We needed the outsider to inspire us,” Bill Flynn replies.

Susan Navarre

Executive Director, Fitchburg Historical Society

People fall in love with history in different ways. It was a Rachmaninoff concert for Susan Navarre, Executive Director of the Fitchburg Historical Society. She was astonished to learn a pianist of his caliber travelled to Fitchburg in 1927 to play in Fitchburg City Hall. “They had Rachmaninoff playing his own work. That’s just extraordinary for a city of 40,000 people, just extraordinary.”

“Fitchburg was the Silicon Valley of the 19th Century,” Susan says. “People were ambitious. We have so many stories of people who started out as factory workers. They saved some money, and then two of them would go off on their own. There’s something exciting about that. When I was younger, that was my understanding of how history should be told. It would be all this fawning on a couple of families that were really wealthy and gave cities all this stuff. But unless it’s your family, that’s not wildly interesting. The story becomes your own when you see something you recognize. Like, this is where I grew up, and this is my grandmother’s.”

Susan realized that nuances could bring history to life. “People often email us, saying: ‘We’re coming to the United States, and we’re going to New York and to Fitchburg.’ They are searching for their histories.” And when they arrive, they place historical facts into a personal context.

“We are not only a history museum.” The Fitchburg Historical Society is an information hub, a repository of artifacts and ideas that help connect individuals within the community. People come here to learn the age of their house, their grandparents’ experiences, the residual implications of discrimination, and who participated in The Underground Railroad. “Knowing history, real history, and telling the truth about history is important to our culture.” And owning a shared history nurtures primal bonds – even among strangers. These bonds are the stuff around which communities coalesce.

The Fitchburg Historical Society’s holdings are vast. “I have been told we have 200,000 discrete items,” Susan says. “More arrive on a weekly basis.” With only one other part-time professional, Loretta Kline, and volunteers, theirs is a labor of love to fulfill information requests. The Fitchburg Historical Society receives as many as 9,000 visitors per year. Susan smiles: “You never know what will be important.”

Francisco Ramos

Director of Community Organizing, NewVue Communities

Francisco Ramos, activist and community organizer, experienced political awakening while working with Central American refugees against the backdrop of Contras and revolution. He recalls being stationed in El Salvador in 1988: “Very tough times … and in the middle of a civil war.” It was a trial by fire. “Returning to the States, I recycled myself from issue to issue. Fair and affordable housing, public health, labor rights, tenant rights, you name it.”

There are two throughlines in Francisco’s formative experience. First, he was an advocate for small-voiced people. His role was that of a champion battling for a community’s interests. And second, there was always an adversary. Whether this was a municipal government, a landlord association, or a health insurance company, there was always an opponent from whom he had to wrest concessions. His gain would be their loss.

Skip ahead to 2018, when Francisco joined NewVue Communities, where he is now the Director of Community Organizing. “Traditional organizing is about building power … finding targets and issues,” Francisco says. It is about confrontation. “But here, in Fitchburg, the dynamics are different. Everybody is on the same side. Everyone is working together to revitalize the community. The shared goal is to fuel economic and social progress through housing development, home ownership, small business development, and community organizing.”

Francisco Ramos is realizing this goal with a two-pronged approach: he elicits resident engagement and grooms community leaders. My job, he says, is to “help people grow, develop expertise, and follow their dreams.”

Digi Chivetta

Multi-media Artist

“I moved to Fitchburg from Northborough,” Digi Chivetta tells me. In 2022, she responded to an open call for public art at Fitchburg Abolitionist Park, and the sponsors awarded her a multi-painting project. “My mural depicts a little black girl. She’s crying. A woman wipes tears off her face.” The image is personal. “When I was that girl’s age, I never saw anyone who looked like me in any museum or public art. Anywhere. Ever. So, I wanted kids in this generation to have a different experience. I want kids to know that our community values their presence.

“Once I got that job, I discovered other opportunities here,” she tells me. The Fitchburg Art Museum invited Digi to participate in the Dialogues, Diasporas, and Detours through Africa exhibition, where she presented her fashion work as well as paintings. “I made so much work for that exhibition. They were only able to show about 20 to 30 percent of it. So, after your first museum exhibition, the next thing for your career is to have a solo show. But I couldn’t think of a location that had enough space, and that would let me have a solo show.”

“I am not just an artist; I am also a hustler.” Digi is now creating her own pop-up museum, this one in the form of an art walk through Fitchburg. “I have seven different business locations that will be hosting my work. I’ve custom-designed a gallery space for each. I chose a variety of businesses so that if people are coming from out of town, they can make a whole day out of it. I have a restaurant, a bar, a flower shop, a metaphysical shop, Curious Escape Rooms, Fitchburg Historical Society, and First Parish Church. They’re all on Main Street.”

Digi’s endeavor serves other goals, too. “One of my ideas is to bring more tourism to Fitchburg and more customers to the businesses. And another is to give the people of Fitchburg a place to connect. But beyond that, kids today seem to live such regimented lives. They have so little freedom and little opportunity to socialize with each other outside school and social media. I want to give them something they can do and talk about with each other.”

“It’s not any easier for me than anybody else,” Digi Chivetta says. This artist has ideas, and she is doing something with them.

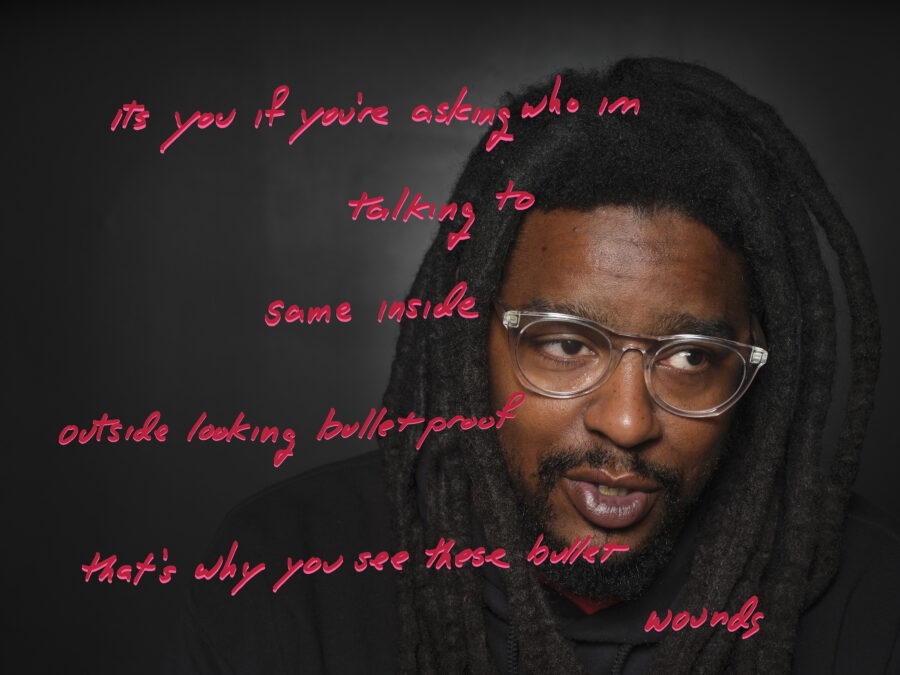

Derek Craig, aka Yo Daddy Doe

Musician and Producer, Young Coff33 Productions

“The darkest part of my life was also the most enlightening. It gave me purpose, which is probably why I am talking to you today.”

Derek Craig discovered his passion as a teenager. That is when he first started to write music. Born in Fitchburg, and a local Massachusetts native throughout, he experienced culture shock attending college in Texas. Everything was unexpectedly comfortable. It was the first time he was not a member of a social minority. He discovered peers and role models. He fell deep into his medium: rap, poetry, and lyrics. In 2019 he opened his own production company, Young Coff33 Productions.

Upon graduation from college, Derek swallowed the bait and entered corporate life. Working for a major lighting company, he traveled up and down the East Coast and into the Midwest. He honed his organizational skills, rising to the position of Project Manager. An unplanned event led him to change course and pursue music and music production full-time. “I’ve grown to understand that managing things creatively is another art form,” he says.

Some people are attracted to Derek because of his music, how he thinks, what he says, or how he says it. Others come because of the platforms he is creating. “We empower other creatives,” Derek tells me. “Our radio, our medium is our music. Without organization, it can’t go anywhere. Our goal is to help creatives understand the business of music.”

“Ricardo, I don’t think you know this,” Derek volunteers. “I am blind. I have no vision in my right eye, and the little in my left is tunnel vision.” Glaucoma robbed Derek of his sight at the age of 27. This is challenging enough, but Derek Craig is also a man of color in a predominantly white society and living in a State where the audience for rap is scattered.

“It is hard to make a living as an artist. I am an Art Steward, a member of Fitchburg’s creative economy, yet I recognize the tokenism I am currently playing, even among my well-meaning friends,” he says. “But I am also a leader of my community, however small. As a minority, sometimes you get stuck in a pigeonhole and can’t say anything because, later on, you might need help from one of the other leaders. You might need one of them in your corner. Minorities are forced to struggle with their own resentment if they want to get anything done.”

“So how do we change the narrative?” Derek asks, then answers his own question. “To begin with, be honest. I try to do that in my music. Say it like it is. Look in the mirror and really see the ecosystem that we live in. Identify the systemic structures shaping – or failing to shape – the opportunities within each niche of our community.”

To which I’ll add: have the courage to raise your flag and rally your peers like Derek Craig.

Brendan McWilliams

7th Grade Public School Teacher

Gaetana Montesion arrived in America through Ellis Island in 1914 at age 20. She made her way to Fitchburg, where she met her future husband, Francesco Zichelle. Francesco had immigrated two years earlier, at age 18. While the two had not previously met, they were both from the same hometown, Lacedonia, in southern Italy.

Like all immigrants, the two had high hopes for the future. When World War I interrupted their plans, Francesco enlisted in the US Army Air Service. Upon his return, he found employment as a trolley conductor, then a paper mill employee, and eventually opened a photography studio on Main Street. Gaetana and Francesco were married in 1919. One hundred years later, their great-grandson, a young professional with a graduate degree, lives in a grand Victorian on a hilltop overlooking the city.

An ornate column rises at the foot of the main staircase in this house. It is an exclamation mark emphasizing the intricate relief along its side wall. Hardwood flooring spills from one room into the next. This house was a statement of wealth and taste in Gaetana’s day. Surely, as she passed through Ellis Island, Gaetana hardly dreamed such a house would one day belong to her children and their descendants.

“I bought this house from my grandparents,” Brendan McWilliams tells me. “My grandmother was Gaetana’s daughter. I have fond memories of playing here as a child.” Brendan was born in Fitchburg and attended its public schools. He also fondly remembers a high school teacher, Miss Vuola Bicoules, who continuously challenged him to do better. “She grabbed your attention, so you were fascinated by everything that was happening.”

“I liked school. I thought that if I became a teacher, I would never have to leave it. I got my degrees at Fitchburg State University. I loved it there. Everybody knows you. You’re not a number.” And that attitude is what Brendan brings to his work every day.

“I teach 7th grade in the Fitchburg public school system,” Brendan says. “English Language Arts. It’s about reading and writing. We were pretty heavy on poetry this past year, but we’ve done a lot of short stories and articles on social media and its influencers to decipher what blurs the line between reality and what’s not real.” When the kids write argumentative essays, “I always tell them that if they can make an argument and present the best evidence supporting what they’re saying, then they’re right.”

“Do you have any students you perceive as promising writers,” I ask.

“Oh, yes, most of them. But I also understand that some are late bloomers, and I don’t give up on any of my kids.”

“What gives you the most satisfaction?”

“The look on somebody’s face when they finally get it. Because when they say, ‘Well, I don’t get it.’ I always say you don’t get it yet. ‘Yet’ is the key word. You will. I promise you will.”