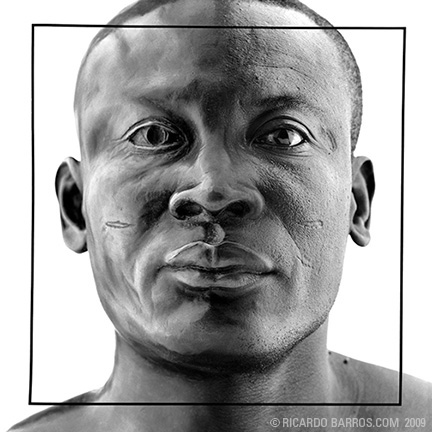

Joseph Acquah is a native of Ghana. Lots of people ask, so let me mention this detail first: he has ritual scars on both cheeks. Joseph works at a sculpture foundry near my studio; we met when he commissioned me to photograph his artwork. I remember two of my observations when he delivered his sculpture. First, nearly all of the sculptures were highly realistic. Second, he was an extremely pious man. As carefully as Joseph might render the detail in one of his sculptures, he is profoundly aware that The Almighty perfected the original and we men cannot improve upon His work.

Joseph Acquah is a native of Ghana. Lots of people ask, so let me mention this detail first: he has ritual scars on both cheeks. Joseph works at a sculpture foundry near my studio; we met when he commissioned me to photograph his artwork. I remember two of my observations when he delivered his sculpture. First, nearly all of the sculptures were highly realistic. Second, he was an extremely pious man. As carefully as Joseph might render the detail in one of his sculptures, he is profoundly aware that The Almighty perfected the original and we men cannot improve upon His work.

One of the pieces Joseph brought to my studio was a self-portrait. When I looked at this bronze bust, I didn’t see metal. I saw Joseph.

After I had made all of the photographs of his artwork that Joseph needed, he agreed to let me make a few more pictures for me. I sequentially photographed Joseph and his bronze bust from exactly the same perspective. Later, in the darkroom, I blended the negative of the left side of Joseph’s face with that of the right side of his sculpture. Perceptual agreement within the combined image was almost too convincing. The photograph could easily be mistaken for an Avedon-like tribute – a Black man photographed against a white background – which meant that many viewers might not even notice Joseph’s accomplishment.

I realized that I would need some sort of visual friction to resist too quick a read of this photograph. I found it in the square, a simple form whose four sides reflect a perfect symmetry suggestive of Joseph’s own inspiration. I ran black tape along the surface of a white tabletop and photographed the outline it produced. I returned to my darkroom and optically blended all three negatives into a single image. (The left side of Joseph, the right side of the bronze, and the outlined square.) The resultant, silver print was my completed artwork.

Later, with the advent of digital imaging, I acquired the ability to replicate this blending process on a computer. It is far easier to merge digital images than to optically blend Black and White negatives. But the new technology also presented me with a choice. In evaluating the subsequent ramifications, I stumbled upon new insight into Joseph’s portrait.

The computer afforded me far more control than I previously had in rendering the design element, allowing me to redraw the black lines with utmost digital precision. I was able to lay down lines that did not waver. My corners met at exactly 90 degrees and had clean, orthogonal edges. But these ‘improvements’ did not make the photograph more beautiful! They had the opposite effect – they made the image more sterile.

The digital alternative made me appreciate that a living, breathing soul had passed his hand along the table’s surface, and warmth within that gesture underlay the wavy lines of the original square. I discarded the digitally generated square and scanned my original negative of the taped tabletop, flaws and all, to produce my digital print.

For me, that simple, taped square makes a statement of metaphoric proportions. It is far more powerful in its imperfect state because it reveals the trace of human intervention.